The New Frontiers of Circularity: the legislative contribution to accelerate the transition

From the AGEC Law in France, to the Digital Product Passport: Europe at the frontline for sustainable development

Viktoriia Shiriaeva, Presales Specialist of Deda Stealth

The

principles of the circular economy, from reusing to repairing and

recycling, represent the future of fashion (and beyond) and the most reliable

answer for the next generation's well-being. The circular economy, in

contrast with the linear model, is a system that aims to reduce waste and

trash by reintroducing materials and items back into the production cycle

at the end of their life span. The belief behind this model is that every item

is born to live multiple lives.

Why is it crucial?

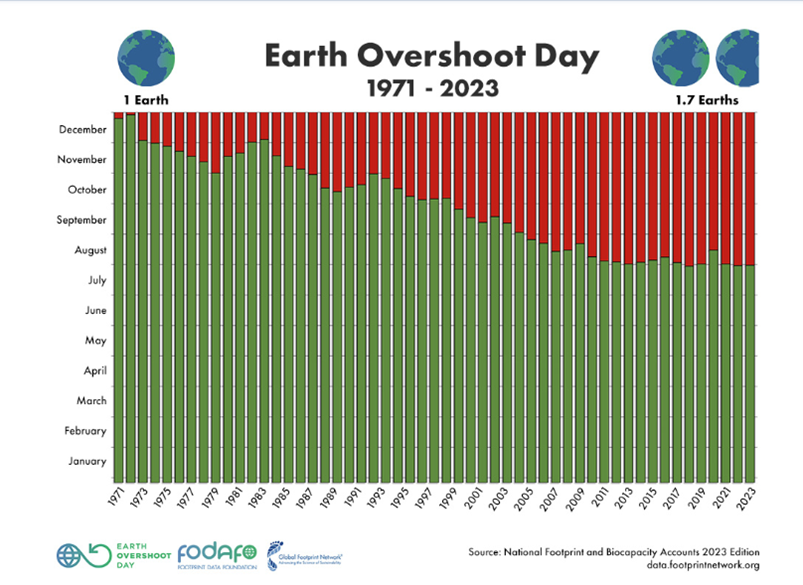

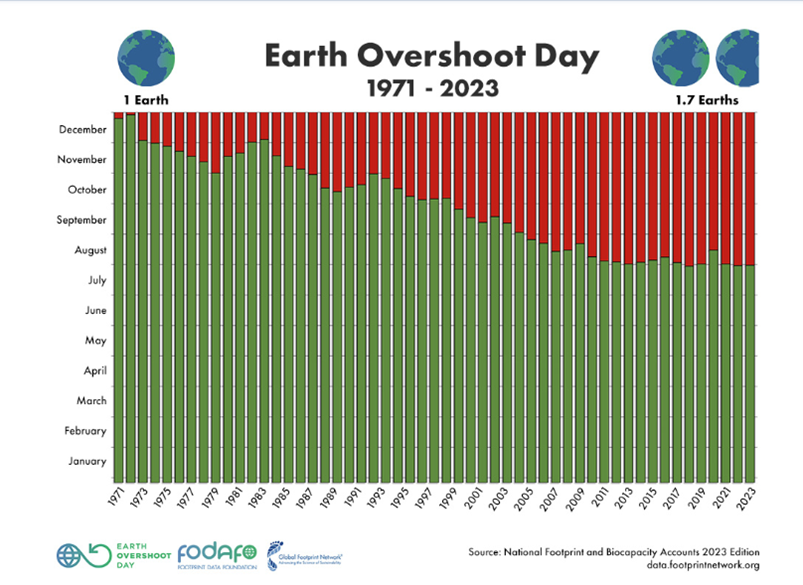

The chart

below shows the Overshoot Day i.e., the day of the year when the

consumption of all the resources produced by the planet is determined. This parameter has been recorded from the 1970s till 2023.

This year's earth overshoot day has been predicted for next August 2nd. Meaning that on that date it is estimated that we will run out of the resources that our planet can produce in one year, and therefore for the remaining time in 2023 we will be "borrowing" resources on the following year, basically as if we had one and a half planets instead of one.

Traceability and Transparency: the enablers of a circular economy

The

circular economy fits into this context as one of the possible solutions to

look at, and significant contributions are coming from governments

worldwide, especially in the fashion industry. Starting from January 2022, in

fact, the obligation to collect textile waste separately has been

introduced in Italy, which is a law that will come into effect by 2025 at the

European level as well. These initiatives aim to facilitate the reuse and

recycling of waste to slowly get to the point where waste is reduced to the

bare minimum. Other legislative and regulatory initiatives address the two

enabling factors for the circular economy: transparency and traceability.

The AGEC

law in France, which was created with the aim of transforming linear economic

models into circular economy systems, is applied in several areas of

intervention: decreasing the use of plastics, punctually informing consumers,

reducing waste in favor of recycling, and making the production chain more

transparent and traceable. On the other hand, the "Kreislaufwirtschaft" (German Circular Economy Act) directive focuses mainly on separating and recycling industrial and household waste. Finally, introducing the DPP (Digital Product Passport) will change the

management and retrieval of product information, supporting the principle of

data economy.

The

European Commission wants to accelerate the circular transition, following up

on the goals set by the Green Deal. The DPP will provide information

on the composition of products circulating on the European market, to

increase the possibilities for reuse or recycling.

According

to the new regulation, the product passport will:

1. Ensure

that actors along the value chain, including consumers, can access information

about the product they are interested in.

2. Improve the traceability of products along the value chain.

3. Facilitate

the verification of product compliance by competent authorities.

4. Include

the necessary data attributes to enable traceability of all hazardous

substances throughout the life cycle of the products involved.

The idea is to provide supply chain players with all the data they need to understand better how to properly dispose of any waste or give new life to products. Probably the DPP could finally highlight the many cases of "False Green Claims," better known as Greenwashing cases, helping consumers orient their purchasing choices, and consistently rewarding those production realities that, with so much commitment and determination, try to embrace circularity and sustainability logics.

Sustainability: a factor to be considered from product conception

There are

already virtuous examples to be inspired by. A few months ago, I had the good

fortune to visit the production plant of a Tuscan company. It has been quite a

source of hope for the transformation of the industry. The company's core

business is woolen garment production, but it also devotes part of its

activities to textile production. This Tuscan business was born during World War

II when there was a need for new garments, but there were not enough raw

materials. The special feature, in fact, is that virgin raw materials are not

used, but rather the production waste of others or those coming from textile

waste, collected and sorted by color and composition.

Wool (as

well as some other natural materials) has a strong regenerative capacity. In

fact, its fibers are strong and flexible enough to withstand not only years of

use but also 100 percent recycling (and multiple times). A unique process was

created to destroy the used garment, create a "recipe" of color and

mix wool fibers of various shades in order to achieve the desired result of the

new yarn. This is certainly an ingenious vision: not only is virgin wool preserved,

but the huge amount of water that would normally be needed to dye the yarn is

saved.

This logic

of circularity, for example, has been applied for years in the furniture

industry: starting from the similar need to make maximum use of scarce

resources and produce excellent results. Eventually, the scarcity of

resources can be an opportunity and sharpen one's genius.

Circularity at risk

The circular

economy can only be part of the long-term solution, but attention must be

paid to the fact that even if this approach is taking future waste into

account, it does not prevent it. The volume of textile waste is huge, although

consumers often struggle to perceive it.

Donations of clothing made in the

global south, usually do not get to be reused for 3 main reasons:

1. They are

not useful clothes in that particular region of the world;

2. The

quality of the clothes is low and does not allow reuse;

3. They are

too many compared to the demand.

Most

textiles used today are not of natural origin. Therefore, they alone can never

be disposed of in the environment. At the same time, however, if recycled at

the end of its life, it requires the least consumption of resources (compared

to production from scratch). In addition, we must always take into account the

complexity behind an "organic" production approach, because the

cultivation of cotton, a natural fiber, requires very high-water consumption

and uses a lot of land. So, while being natural, it does not guarantee zero

impact. Furthermore, another aspect concerns synthetic fibers: nowadays, there

is no full knowledge of any technique for recycling them, nor for making these

fabrics less harmful to the environment (e.g., depolymerization that prevents

the release of microplastics).

Whether it

is because of high costs, or the difficulty of sourcing low-impact raw

materials, circularity is not always easy to implement. Moreover,

focusing exclusively on the end-of-life of garments is not enough, because circularity

requires a holistic approach that starts upstream in the value chain, that

is, to make the product have a second life, and already at the design

stage it is necessary to consider this aspect. A product itself can never

be called "sustainable" if it is created following a business model

that is not. The increase in circularity cannot be directly proportional to the

increase in production, but on the contrary, it must make up for the excessive

use of the available resources, and at the same time it cannot be an excuse to

continue producing as before ("we recycle it later anyway").

Sustainable growth: why collaboration plays a crucial role

One of the 5Ps

of the 2030 Agenda goes under the heading "Partnership." Yes,

because to realize and enhance the best practices of sustainable development

and the green economy in the best possible way, continuous discussion

among the various stakeholders in the value chain is necessary.

The new

priorities of agility, transparency, traceability, and continuous dialogue are

touching various parts of the Supply Chain. This is precisely where the

need for a single ecosystem comes from, one that allows the exchange

of information, approaches, and inspirations that all lead to the same

goal: to build business models in line with the needs of sustainability for the

preservation of the planet.

Deda

Stealth, for

instance, is part of the Monitor for Circular Fashion, an active, concrete,

and diversified community with the values of collaboration and sharing at its

core, promoted by SDA Bocconi School of Management in Milan. Participants

in the project include brands, manufacturers, suppliers, and standards

consultants for industries and technology providers. While there is normally a

form of competition among fashion players, overcoming the challenge of climate

change requires everyone to work together and share best practices and

knowledge.

The "Monitor"

complements the classroom plenaries with a traveling itinerary that allows each

member to deepen and better understand the realities of other players and share

sectoral issues and propose sustainable solutions. In addition to the

continuous exchange of information and approaches, there is a concrete attempt

to include the practices of traceability and circularity in the companies. Several

pilot projects have been implemented in recent years, applying the principles

of traceability and circularity and demonstrating that the industry can be

transformed. The challenge in the coming years is to make these pilot projects industry-approved.

The urgency

of transformation is, by now, clear. The industry needs an evolution of

procurement processes and, not least, internal processes as well. We are

certainly talking about a complicated and ambitious challenge, but with the

support of technological development and digitalization, companies can apply

less resource-consuming production models and incorporate traceability and

transparency practices to their supply chains.

For

additional insights on the topic, we recommend the webinar "Digital

Product Passport, Incoming Legislation and the effects on Fashion Supply

Chain" (available here).